This top-to-bottom guide gives an overview of spinal anatomy and the potential problems that can cause pain. Understanding your spine's anatomy and inner workings can help you better manage neck or back pain.

Your spine is mostly comprised of 3 general regions:

- The cervical spine contains 7 vertebral bones that run from the base of the skull down through your neck. This region of the spine has a natural inward curve (toward the front of the body), called a lordotic curve. It supports the head above and is relatively mobile, which also makes it more prone to injury.

- The thoracic spine contains 12 vertebral bones, with the top 10 solidly connected to the rib cage and the bottom 2 connected to floating ribs. This region of the spine runs through the middle back and is relatively rigid to help protect internal organs within the rib cage. The thoracic spine naturally curves outward (toward the back of the body), called a kyphotic curve.

- The lumbar spine contains 5 vertebral bones that form a lordotic curve (same as the cervical spine) and run through the lower back. The lumbar spine is more mobile than the thoracic spine yet also carries more weight, making it the most likely region of the spine to become injured and painful.

Muscle Strains And Spasms

The spine’s vertebral bones are supported in large part by soft tissues such as muscles, tendons, and ligaments. When the back or neck becomes painful, especially short-term acute pain, it is typically due to a muscle strain or ligament sprain.

Muscle strains and ligament sprains can occur from overuse or overexertion, such as from a sports injury or whiplash. While these types of injuries typically start to feel better within a few days or weeks, the pain can be severe.

Painful spasms—with one or more muscles uncontrollably and repeatedly contracting—can develop in the neck or back in response to strain or possibly due to another underlying medical condition, such as osteoarthritis or a herniated disc.

Facet Joint Pain

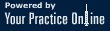

Throughout the spine, adjacent vertebrae are connected in the back by a pair of facet joints. These joints are lined with smooth cartilage to help facilitate restricted gliding movements. While these facet joint movements are small at each spinal level, they can add up to give a significant range of spinal motion for twisting, forward/backward, and side-to-side bending.

The facet joints are a common source of chronic neck or back pain. Facet joint osteoarthritis can occur when the protective cartilage starts wearing down over time. It is also possible for the facet joint to become injured due to a fall or collision.

Discogenic Pain

Between adjacent vertebrae sits an intervertebral disc, which provides mobility and shock absorption for the spine’s vertebral bones that are stacked atop each other. Each intervertebral disc contains:

- A durable outer layer called the annulus fibrosus

- A soft inner layer called the nucleus pulposus

Discogenic pain is considered when pain stems from the disc itself, which can develop due to a crack or tear in the disc. In cases when the annulus fibrosus tears and the disc’s nucleus pulposus and inflammatory proteins start to leak outward, it’s called a herniated disc.

A disc can become painful due to an acute injury or degeneration over time.

Spinal Nerve Compression

At each spinal level, a pair of spinal nerve roots branch off the spinal cord to help send and receive signals with their side of the body. For example, a spinal nerve branching off through the cervical spine may help provide sensation and power to the arm and/or hand, whereas a spinal nerve branching off through the lumbar spine may help innervate the leg and/or foot.

Foraminal stenosis, or narrowing of the intervertebral foramina where the spinal nerve roots exit the spine, can pinch the nerve and cause radiating nerve root pain, numbness, or weakness to travel into the arm or leg. Common causes of foraminal stenosis include facet joint osteoarthritis, degenerative disc disease, or a bulging or herniated disc.

It is also possible for central canal stenosis to cause the spinal cord to become compressed, which can lead to myelopathy with neurological deficits developing anywhere beneath the level of compression. When the nerve bundle that descends from the spinal cord becomes compressed, cauda equina syndrome can occur with leg weakness, saddle numbness, and bowel/bladder dysfunction.

Any type of pain, tingling, numbness, or weakness that radiates into the arm or leg requires immediate medical attention.

The Base of Your Spine Can Cause Pain Too

Below the lumbar spine is a bone called the sacrum, which makes up the back part of the pelvis. This bone is shaped like a triangle that fits between the two halves of the pelvis, connecting the spine to the lower half of the body.

The sacrum is connected to a part of the pelvis (the iliac bones) by the sacroiliac (SI) joints. Pain here is often called sacroiliac joint dysfunction.

The coccyx, or the tailbone, is at the very bottom of the spine. Pain here is called coccydynia and is more common in women than men.

Precision Pain Care and Rehabilitation has two convenient locations in Richmond Hill – Queens and New Hyde Park – Long Island. Call the Richmond Hill office at (718) 215-1888, or (516) 419-4480 for the Long Island office, to arrange an appointment with our Interventional Pain Management Specialist, Dr. Jeffrey Chacko.